Railway Development - a guide to dating maps.

As an aid to dating the various states of printed maps; the

following tables show the lines and their opening dates. Please let me know if there are inaccuracies.

A state signifies a change to the original map after it was first published. Victoriam maps were typically updated with new railway information, however, this was not always correct. See my article in a later page.

|

1

|

01.07.1843

|

Taunton

/ Beambridge

|

9

|

04.07.1866

|

Newton

Abbot / Moreton Hampstead

|

|

|

01.05.1844

|

Beambridge

/ Exeter (St Davids)

|

10

|

16.03.1868

|

Seaton

Jn / Seaton

|

|

|

30.12.1846

|

Exeter

/ Newton Abbot

|

11

|

01.05.1872

|

Totnes

/ Ashburton

|

|

|

20.07.1847

|

Newton

Abbot / Totnes

|

12

|

01.11.1873

|

Barnstaple

/ Dulverton/Taunton

|

|

|

05.05.1848

|

Totnes

/ Plymouth

|

13

|

20.07.1874

|

Barnstaple

/ Ilfracombe

|

|

|

22.06.1859

|

Plymouth

/ Saltash (bridge opened 02.05.1859)

|

14

|

06.07.1874

|

Sidmouth

Junction / Sidmouth

|

|

2a

|

12.06.1848

|

Tiverton

Junction / Tiverton

|

14a

|

15.05.1897

|

Sidmouth

/ Budleigh Salterton

|

|

2b

|

29.05.1876

|

Tiverton

Junction / Hemyock

|

14b

|

01.06.1903

|

Budleigh

/ Exmouth

|

|

3

|

18.12.1848

|

Newton

Abbot / Torre

|

15

|

20.01.1879

|

Halwill

Jn./ Holsworthy

|

|

|

02.08.1859

|

Torre

/ Paignton

|

|

21.07.1886

|

Launceston

/ Halwill Jn.

|

|

|

14.03.1861

|

Paignton

/ Churston

|

|

10.08.1898

|

Holsworthy

/ Bude

|

|

|

10.08.1864

|

Churston

/ Kingswear

|

16

|

09.10.1882

|

Heathfield

/ Ashton

|

|

3a

|

28.02.1868

|

Churston

/ Brixham

|

16b

|

01.07.1903

|

Ashton

/ Exeter

|

|

4

|

12.05.1851

|

Exeter

/ Crediton

|

17

|

11.08.1883

|

Yelverton

/ Princetown

|

|

|

01.08.1854

|

Crediton

/ Barnstaple

|

18

|

01.05.1885

|

Exeter

/ Tiverton

|

|

|

02.11.1855

|

Barnstaple

/ Bideford

|

|

1884

|

Tiverton

/ Bampton

|

|

|

18.07.1872

|

Bideford

/ Torrington

|

19

|

02.06.1890

|

Bere

Alston / Callington (Beer to 1898)

|

|

4a

|

1925

|

Torrington

/ Halwill

|

20

|

02.04.1849

|

Plymouth

/ Millbay (goods) serving Cornwall from 04.05.1859

|

|

5

|

22.06.1859

|

Plymouth

/ Tavistock (South)

|

21

|

19.12.1893

|

Brent

/ Kingsbridge

|

|

|

01.07.1865

|

Lydford

/ Launceston (officially 01.06.)

|

22

|

01.01.1897

|

Plymouth

/ Turn Chapel

|

|

6

|

19.07.1860

|

Axminster

/ Exeter (LSWR, Queen St)

|

|

17.01.1898

|

Turn

Chapel / Yealmpton

|

|

7

|

01.05.1861

|

Exeter

/ Exmouth

|

23

|

11.05.1898

|

Barnstaple

/ Lynton

|

|

8

|

01.11.1865

|

Crediton

/ North Tawton

|

24

|

24.04.1901

|

Bideford

/ Westward Ho!

|

|

|

03.10.1871

|

Okehampton

|

24a

|

01.05.1908

|

Northam

/ Appledore

|

|

|

12.10.1874

|

Okehampton

/ Lydford (orig. Lidford)

|

25

|

24.08.1903

|

Axminster

/ Lyme Regis

|

|

|

02.06.1890

|

Tavistock

/ Plymouth (LSWR)

|

|

|

|

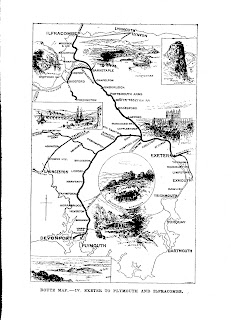

Railways of Devon - from Batten & Bennett The Victorian Maps of Devon

Railways

The railway entered the Devon countryside in the 1840s and their development coincided, more or less, with the period of Queen Victoria´s reign. Before she acceded there were no steam rail lines (but there were mineral railways worked by horses) and at the end of her reign the Devon network was largely complete. The rise of rail has been covered in The Victorian Maps of Devon and reproduced , suffice it to say that even later editions of pre-Victorian works were often altered to include railways and a brief overview of the completion dates for main lines is given here as a rough guide only.

The Development of the Railways in Devon

The earliest railway in Devon was probably John Smeaton’s track in Mill Bay, Plymouth (1756-9). Too short to appear on any map, it was fully described in Smeaton’s book of the Eddystone.[i] He devised his ‘rail road’ to facilitate moving the one-ton blocks from mason to mason, then to the test bed and on to the boats. It was a simple narrow gauge track based on the colliery designs of the time and presumably used man or horse power for propulsion.

John Rennie, the well-known civil engineer, used a 3ft 6in railway when he was constructing the Plymouth Breakwater (1812-1844). The track was used to bring stone from the quarry at Pomphlett down to the quay at Oreston, all three and a half million tons of it.[ii]

The first tramway was on the 'inclined plane' from the Tavistock canal to Morwellham opened in 1817. It was worked by a water wheel supplied from the canal itself. Morwellham Quay largely served the Devon Consols mine. The area both east and west of the Tamar at this point was to become the most important mining area in the United Kingdom and for some minerals the world's leading source. By 1900 some seven hundred and fifty thousand tons of copper alone had been exported through Morwellham Quay from the Devon Consols Mine.[iii]

The first real line was the Heytor Granite Tramway which opened in 1820 and connected the quarries at Heytor to the Stover canal at Ventiford. The track was constructed with two granite ‘rails’ which lay inside the wagon’s wheels preventing the horses from deviating left or right. Trains were made up and were pulled by as many as twelve horses. The tramway was shown on many county maps, for example Greenwood in 1827 and Archer/Dugdale in 1842. The line closed in 1858 and although then omitted from most maps the hard granite tracks can still be seen today.[iv]

In 1820 William Stuart, then the Admiralty engineer with Rennie at Plymouth, was appointed as the part time engineer for the Plymouth & Dartmoor Railway.[v] This second tramway ran from Princetown to Plymouth and was incorporated in an act of 1819 for the line as far as Crabtree, and again in 1820 extending the line to Sutton Pool. It was opened in September 1823 and was the first line to use the 4ft 6in., or Dartmoor, gauge to be followed by the Lee Moor line in 1854. The line was the brainchild of Sir Thomas Tyrwhitt, an eccentric yet successful politician, who lived at Tor Royal, near Princetown. He published a pamphlet in 1818 in an attempt to persuade the Plymouth Chamber of Commerce to join him and construct the new line. He believed passionately that his railroad would ‘gratify the lover of his country; reward the capitalist; promote agricultural, mechanic and commercial arts’. Although he spent large sums to improve the moor the only real use made of the line was to export granite from the quarries, near Princetown, down to the Cattewater. A portion of the line was on a gentle downhill slope where the full waggons ran under their own weight, otherwise the locomotion was provided by horses. The line was first shown on the Greenwoods' map of 1827 (96) along with Heytor and was usually shown on the later county maps. At first it had nothing to do with the prison which had been closed in 1816 at the end of the war, and was not re-opened until 1850 The route above Yelverton was bought by the GWR and redeveloped as a separate line in 1883. It was on this line that in 1891, the year of the great blizzard, a train was stranded for two long nights. The lower length was used occasionally until 1900. A branch line was added in 1833 to run to the blue slate quarry in Cann Wood owned by the Earl of Morley, in return for his earlier agreement for the Plymouth & Dartmoor line. To facilitate the development of the china clay works at Lee Moor a further branch line was proposed and this was built as far as Plympton in 1834. However, local opposition stopped further progress and it was not until 1854 that the Lee Moor railway was built from the clay works to the branch line at Cann Wood. The line again used horses but included two incline systems. In 1899 steam locomotives replaced the horses at the Moor end.[vi]

In 1831 the merchants of Bideford and Okehampton raised funds for a report on the feasibility of a railway between the two towns. In October Roger Hopkins completed a survey and produced plans, books of reference, costs and a full report for lines from Okehampton to Torrington and Bideford. His scheme proposed a narrow gauge track and the use of two steam engines. This would have been the third line in the country, following the diminutive Stockton & Darlington and the Manchester-Liverpool lines of George Stephenson in 1830. In 1831 a House of Commons Committee reported in favour of the use of steam engines on roads and completely ignored the railway. The Bideford to Okehampton line was not to be and by 1836 some of its promoters were diverted to 'Stephenson's line', the L&SWR line from a point between Basingstoke and Winchester to Exeter and thence to Plymouth and Falmouth. Part of the Hopkins' scheme was reintroduced in the proposals of 1845 when his sons proposed a line from Tavistock (the South Devon Railway from Plymouth) to Okehampton and then with a branch to both Bideford and Crediton (the Exeter & Crediton railway). But this too failed when the South Devon Railway decided not to extend their line to Tavistock.[vii] Although these schemes always included full drawings the lines apparently did not appear on any county map, probably because no act was proposed in parliament.

The development of steam railways in the West Country almost exactly coincides with the reign of Queen Victoria. The line to Bristol was operational in 1841 and by 1901 only four small branch lines were still to be opened in Devon. In just two generations the life of the county was altered and the effect of the railway on travel to and within the West Country was dramatic.

In 1780 it took nearly two days to travel from Exeter to London. By 1826, with the advent of the post roads, the stage coach Telegraph took seventeen hours; and the Quicksilver sixteen and a half hours on its way to Plymouth, which was reached some four and three quarter hours later.[viii] There were only two fast coaches a day and each could carry only ten passengers, four of whom were outside!

But with the coming of the railway travel changed forever. On 1 May 1844 the first through train reached Exeter. ‘We had a special train with a large party from London to go down to the opening. A great dinner was given in the Goods shed at Exeter Station. I worked the train with Actaeon engine, one of our 7-ft class, with six carriages. We left Exeter at 5.20 pm and stopped at Paddington platform at 10. Sir Thomas Acland, who was with us, went at once to House of Commons, and by 10.30 got up and told the House he had been in Exeter at 5.20.’[ix]

The most dramatic account of the change comes from the notes in Cecil Torr’s book of Wreyland; ‘On 19 March 1841 my father started from Piccadilly in the Defiance coach at half past four, stopped at Andover for supper and at Ilminster for breakfast, and reached Exeter at half past ten’ (eighteen hours later). ‘On 10 October 1842 he started from Paddington by the mail train at 8.55 pm reached Taunton at 2.55 am and came on by the mail coach stopping at Exeter at 6.15’ (nine hours and forty minutes later). ‘20 March 1845 coming on the same train he reached Exeter at 4.25 (seven and a half hours later). On 8 August 1846 he came by the express train, 9.45 am to 2.15pm’ (four and a half hours later).[x]

However, not everyone was so enthusiastic about the advance of the railways. William Collins, the publisher, is known to have chaired a demonstration in Glasgow in November, 1840[xi] protesting against Sunday trains. Many landowners were opponents of railway development. Lord Fortescue objected to a branch from Umberleigh Bridge to meet the Taunton-Barnstaple line at South Molton and the line was never built. Sir William Williams objected that the Ilfracombe line, passing between his house and the river, would damage his property and it was not until 1870 that he withdrew his objections and a year later the line was built.[xii] Hutchings, writing about Barnstaple, complained that: ‘Just below the hideous bridge which carries the South Western line across the Taw is the Quay ... and on the right bank ... is the North Walk, now unhappily cut up for the purposes of the new railway from Lynton’. [xiii] But perhaps the worst comment was written by J Lloyd Page: ‘Within the last four or five years the repose of this valley has been broken by the locomotive ... He is noisy; he is obtrusive. Where he gets his iron foot romance dies. And from Dulverton to Exeter he has spoilt the Exe Valley’. [xiv]

But the railway was not to be stopped. The first proposals for a line from London to Bristol had been made in 1824 yet little was done until March 1833 when I K Brunel was appointed. He not only surveyed the route, he designed the line. Some idea of the undertaking can be appreciated from his diary and correspondence. His own duty of superintendence severely taxed his great powers of work. He spent several weeks travelling from place to place by night and riding about the country by day, directing his assistants and endeavouring, very frequently without success, to conciliate the landowners in whose properties he proposed to trespass. His diary shows that when he halted at an inn for the night little time was spent in rest; he often sat up writing letters and reports until it was almost time for his horse to come round to take him for the day's work. ‘Between ourselves‘, he wrote to Hammond his assistant, ‘it is harder work than I like. I'm rarely much under 20 hours a day at it’.[xv] A great example of his surveying ability must be the Box Tunnel. This is straight for 3193 yards at a constant fall of 1:100 to the west and when clear of smoke one can see through the entire length. It is said that on or about 9th April the sun is visible from the west end before it rises over Box Hill.

The costs were large, not only the compensations for land and the actual construction of line and rolling stock but also for the bills to pass through parliament. The first Bill for the Great Western Railway approved by Parliament cost the company £87,197 or about £775 per mile of line constructed.[xvi]

Initially there was also the problem of time. The GWR timetable of 30 July 1841 contained the disconcerting statement that ‘London time is about four minutes earlier than Reading time, seven and a half minutes earlier than Cirencester and fourteen minutes before Bridgewater’. Although by 1848 most lines had adopted Greenwich time[xvii], this was very much a local problem and was not finally resolved until 1852 when Greenwich time was adopted in the West of England. The Mayor of Exeter issued a notice on the 28th October ‘That upon and after Tuesday the Second Day of November next the Cathedral Clock, and other Public clocks in the city, will be set to and indicate Greenwich Time’.

The GWR scheme was completed, approved by parliament and received Royal Assent in 1835; the actual construction was much quicker and by then Brunel was also working for the Bristol & Exeter Railway; in 1841 the line was open as far as Bridgewater.[xviii] By the 1st of May 1843 it had reached Beambridge, just west of Wellington, then through the Whiteball Tunnel into Devon and, exactly a year later, Exeter: ‘The opening day was kept as a general holiday, all business was suspended, a splendid dejeuner a la fourchette took place at the Railway Station, and vast numbers from all parts of the County came to witness the arrival of the first day's train’.[xix] A local newspaper journalist was even more enthusiastic: ‘intercourse with the more populous districts of England cannot but prove highly advantageous to the fair and lovely spinsters of Devon.’ [xx]

Two routes were suggested for the line to Plymouth; the coastal line through the South Hams and the inland route through Crediton and Tavistock. In 1840 Plymouth merchants proposed a third line, a high-moor railway through Dunsford, Chagford and Yelverton.[xxi] The route was surveyed by Nathaniel Beardmore, an apprentice of J M Rendel, and a final route plan was prepared.[xxii] The estimated cost was £770,780 including the branch to Tavistock, a saving, so it was claimed, of £1,000,000 over the coastal route. But it was too late. Business interests in both cities were concerned over the waste land and that mines and quarries would not provide sufficient income.[xxiii]

As early as 1836 Brunel had surveyed the route to Plymouth and the South Devon Railway bill received Royal Assent in July 1844. In 1846 trains ran to Teignmouth and the sea. So great was the excitement on that Whit weekend when Exeter went to the coast, that ‘upwards of 1,500 persons went down and at Dawlish and Teignmouth bands of music were stationed and flags flew from every tower’.[xxiv]

The route to Plymouth was designed to use the newly patented atmospheric power.[xxv] Stationary engines pumped the air out of an iron pipe laid between the rails, creating a vacuum ahead of the carriage's piston which was propelled by the air behind it. It was claimed to be cheaper and quieter to operate with heavier trains. The first atmospheric train to Teignmouth ran in September 1847 and to Newton Abbot four months later. ‘Many prefer the noiseless track to the long drawn sighs of Puffing Billy’.[xxvi] After the first teething troubles were overcome the system ran well but sadly the valves proved difficult to maintain. The scheme was abandoned in September 1848 and the route changed back to using ordinary steam locomotives.

The line had reached Totnes by February 1848 and to Laira, on the outskirts of Plymouth, by the 5th of May. On that Friday ‘By common consent all business in Plymouth was suspended, banks, shops, and all other places of trade, with but very few exceptions, being closed ... and tens of thousands of persons assembled to greet the arrival of the opening train, gaily decorated with flags, (which had) completed the distance from Totnes in 42 minutes.’[xxvii]

The line from Newton Abbot to Torre followed in December of the same year but work on the branch line was slow. It took eleven years to reach Torquay and Paignton, where a party was held with a pudding weighing over a ton, and it took a further five years to reach Kingswear, opposite Dartmouth. Although South Devon was open it was not until May 1859, just four months before his death at the age of 53, that Brunel completed the Royal Albert Bridge, and the railway line entered Cornwall. Nevertheless, the south coast was quick to exploit the fact that two main lines came into the county. Exmouth trains ran from 1861 and the neighbouring towns of Seaton and Sidmouth saw their first trains in 1868 and 1874 respectively.

At the same time branch lines continued to be built and to be absorbed. Most of these lines were built by local private subscription and were run as separate companies with the South Devon Railway. There was great hope that the lines would open up the county for both passengers and trade. The Torbay and Brixham branch was opened in 1868 to the benefit of the fishing fleet. The south of Dartmoor was opened up to much acclaim. High days and holidays greeted the first trains with celebrations and even tea for the one thousand five hundred residents of Ashburton. The twelve mile line to Moreton Hampstead was opened in July 1866, but not without troubles. The engines on this branch were quite unequal to their work, and there were then no effective brakes. Coming down the incline the trains often passed the station and passengers had to walk from where the train stopped. The last branch of the South Devon Railway was the Totnes-Ashburton line which opened in 1872. This nine and a half mile stretch followed the river (whereas an earlier suggestion - directly from Newton - would have involved some very steep gradients). Although the once flourishing wool industry was in decline the area was responsible for half of Devon's serge trade and Buckfastleigh station was often busier than Newton Abbot.[xxviii] Plans were made for a line from Totnes to Exeter via Ashton and the first stretch was completed in 1882, providing access to the Teign House Races at Christow. It was not until 1903 that the line finally reached Exeter.

North Devon was not so fortunate. Though the Taw Vale Railway & Dock Company was incorporated in 1838, to run a line from Fremington to Barnstaple, nothing happened and in 1845 the extension to Crediton was abandoned as a result of the controversy over the gauge.

This problem affected all the early lines in Devon. Brunel proposed the famous broad-gauge of 7' 0¼" for the Great Western Railway and this was adopted by all the early westcountry companies including the line from Exeter to Crediton.[xxix] Most other railways in Britain, including the London & South Western Railway were using the narrow gauge of 4' 8½" and this was favoured by the Taw Vale.

The two track systems were very different in their construction. The narrow gauge had ‘conventional’ cross sleepers while the broad gauge used longitudinal timbers. Brunel had designed for speed and for comfort. By 1845 the train to Exeter (194 miles) took only four and a half hours and the luxurious, ten feet by seven feet, first class compartments were designed for only eight passengers. But it was not until the LSWR pushed westward that the problems arose, and nowhere was the conflict more real and more damaging than on the line from Exeter to Barnstaple.

In 1845 the Exeter and Crediton line was incorporated and by 1847 their broad gauge line was almost ready. But also in 1845 the Taw Vale line from Fremington to Barnstaple, enacted in 1838 proposed, with London & South Western Railway interests, an extension to Crediton and in August 1847 the line obtained approval but only with broad gauge support. However, by then the L&SWR had bought considerable stock in both lines and their nominees effectively stopped the Crediton line from opening; moreover they proceeded to narrow the track leaving the broad lines to rust.

In February 1848 the Railway Commissioners ruled that the line from Barnstaple to Crediton, the Taw Vale Extension, should be broad. The L&SWR cancelled the opening and halted the construction of the new line. In 1851 the North Devon Railway took over both the Crediton and the Taw Vale lines and leased them to the Bristol and Exeter. The Crediton line was re-converted back to broad-gauge and was opened in May. Work northward commenced in February 1852. Finally, regular service to Barnstaple commenced in August 1854, but the extension to Bideford beyond Fremington was only opened to passengers in November 1855. The time, the cost, and the frustration were enormous. The north of the county had remained virtually isolated while to the south trains had reached Plymouth six years earlier.

The gauge dispute continued until the end of the century,[xxx] aggravated in Devon with the arrival of the London & South Western Railway, whose narrow-gauge lines from Salisbury to Exeter, either by a central or coastal route, received assent in July 1848. After many years of confusion and debate the Salisbury-Yeovil line was agreed and the line to Exeter was opened in July 1860. The Exeter/Crediton line, the Bideford Extension and the North Devon leases were all taken over in 1862 and amalgamated with the L&SWR in 1865. The gauge of this line was mixed and broad-gauge goods trains still visited Bideford as late as 1872.

The county was in a sense split. The North East and South West were developed by the Great Western Railway (God’s Wonderful Railway) and the North West and South East by the L&SWR, crossing at Exeter. There were two anomalies. Both companies were to construct lines to Launceston (closing the Dartmoor Loop), the GWR from Plymouth via Tavistock and Lydford and the L&SWR from Halwill Junction, and both had lines to Plymouth when the L&SWR extended its line from Okehampton through Tavistock and Bere Alston. The Plymouth line introduced a change-over in the town with a stretch of mixed-gauage track and a new station at North Road. Shortly after this the GWR took over the SDR and dissolved it altogther in 1878. There were also two other variations. Brunel’s philosophy for the GWR was for directness. If a town was not in line, so be it. Tiverton was an early example with the town served by the Tiverton Road Station five miles away. On the other hand, the L&SWR were content to have branch lines totally isolated from the main system. A good example was the Bodmin & Wadebridge line in Cornwall which was taken over in 1846, fifty years before it was connected.

By 1865 Devon and the West Country were fully linked, if confusedly, with the rest of England. Tourist tickets from London to the north coast resorts were issued in two parts: Passengers changed to horse-drawn coaches at Taunton for Williton, Lynmouth, Lynton and Ilfracombe. The tickets included the coach fares and all fees to Coachmen and Guards. First class tickets entitled the holders to either inside or outside places, but second class were for outside only. Lynton coaches left Williton station (just south of Watchet) daily, except on Sundays, at 2.50 pm after the arrival of the 9.15 am Express from Paddington. Passengers for Ilfracombe broke their journey at Lynton to continue the next day at 7.0 am.

Trains ran regularly from Paddington to Exeter (four hours and forty five minutes); Torquay (six hours and thirty eight minutes); Kingswear (seven hours and twelve minutes); Plymouth (seven and a half hours); Barnstaple (eight hours and thirteen minutes). Journey times up or down were much the same. Fares were cheap compared to the £3 single to Exeter on the Defiance coach: Paddington to Lynton cost 65s & 46s (1st & 2nd return); Ilfracombe 79s & 56s; Torquay 50s & 37s; Plymouth 58s & 42s.[xxxi]

Times improved and in 1887 the Jubilee Express took only six hours and fifty minutes to reach Plymouth. Service facilities took far longer to improve. Until 1882 there were no toilet facilities on any trains in the country, nor dining arragements until 1893, and it was not until 1887 that a West Country train carried third class passengers.

For a long time the north west of Devon remained untouched by the railway although the Bideford to Torrington stretch had been completed by 18th July 1872. Before the Exeter-Barnstaple line was started the Taw Vale Railway Company had built a stretch for horse wagons from Fremington to Barnstaple to bring cargoes to the railway station (1848)[xxxii] but few people. In 1880 the North Devon Clay Company laid a three foot gauge from Marland to Torrington for the goods and workers of the mineral companies at Marland and Meeth, but it would be the twentieth century before a passenger line would be completed to Halwill. In 1879 a line was built from Meldon, near Okehampton, through Halwill to reach Holsworthy in January 1879. Here for years it rested, while the company decided where to go next. Then instead of turning north to Torrington the line headed west to the sea and Bude, being opened in August 1898. In the meantime the L&SWR completed their connection from Launceston to Halwill in 1886.

The Somerset and Devon Railway (known as the Slow and Dirty) proposed a shorter link from Taunton to Barnstaple which the L&SWR instantly opposed. However, the first turf was lifted at South Molton in 1864 and by 1866 the section to Barnstaple was making good progress. The line opened in sections (Norton to Wiveliscombe in June 1871) but it was not until August 1873 that directors were able to travel the first train from Bristol to Barnstaple via the new line.[xxxiii] Planners obviously saw the chance to provide Tiverton with a through railway at last, and during the years 1884-85 a line connecting Exeter with Tiverton and then Morebath (Bampton) was opened in two stages. Also in the east the branch line to Hemyock was built by the Culm Valley Light Railway to serve Coldharbour Halt, Uffculme, Culmstock Halt, Whitehall Halt and Hemyock, and opened 29th May 1876.

One of the last lines to be sponsored by the two railway giants was the second Tavistock to Plymouth line. The LSWR had been paying high fees to use the GWR line linking the two lines. They were reluctant to build the new line themselves but they provided the funds to the Plymouth, Devon and South Western Junction Railway to build and operate it. Opened in June 1890, it connected Tavistock with Devonport via Bere Alston and, at last, the L&SWR had their own route linking London to Plymouth. As a consequence it was in a good position to steal the lucrative fruit and flower trade of the Tamar valley from the GWR. The line improved official LSWR times from London to Plymouth by thirty to forty minutes for the 229 mile line: but as the trains were frequently late, this was mainly academic.[xxxiv]

One of the later small companies was the Lynton & Barnstaple. It used the narrowest gauge in the county for passenger trains, a mere one foot and eleven and a half inches, and was sponsored almost entirely by local people. Sir George Newnes, head of a famous publishing house (he published Bartholomew's Royal Atlas c.1900) was one of the most supportive advocates of the new line. It was his wife, Lady Newnes, who cut the first turf at the projected site of Lynton station in September 1895.[xxxv] The line was not a success, partly due to the terminus at Lynton being several hundred feet above the village, and it was sold at a loss to the Southern Railway in 1921.

By the beginning of the twentieth century the network was almost complete. In the south the long-awaited route to Kingsbridge was opened in 1894 - it had been anticipated from at least 1872 - and in 1898 trains ran from Plymouth to Yealmpton. On the North coast the Westward Ho! line was opened in 1901 although it had been planned as early as 1860 and in the centre Bude was finally linked to Holsworthy.

In 1903 lines connecting Exmouth to Budleigh Salterton, Axminster to Lyme Regis and the Ashton to Exeter route were completed. In 1908 the Westward Ho! line was extended to Appledore, only to be closed in 1917. This line was not connected to the main Bideford line - one walked over the bridge. The only time that trains crossed the river was in 1917 after the closure, when rails were laid down to transport the rolling stock to its new home. This railway had a remarkable time-table stating that ‘the published time tables ... are only intended to fix the time before which the train will not start, and the Company do not undertake that the trains shall start or arrive at the times specified’.[xxxvi] When in 1915 the army in France began to construct narrow gauge supply lines the tracks of the Appledore railway were taken up and shipped out of Portishead to be sunk by a U-boat off Padstow.[xxxvii]

The year 1908 also saw the line from Bere Alston to Callington officially opened on 2nd March.[xxxviii] The Callington-Calstock Railway was founded in 1869, became the East Cornwall Mineral Railway two years later, and began goods traffic on 7th May 1872. This connected Kelly Bray (just north of Kit Hill and Callington) and Gunnislake with Calstock on the east bank of the Tamar and was vital to the mineral trade in the area. From c.1844 to 1870 both banks of the river experienced a major boom in copper production especially through Morwellham Quay. The value of ore shipped out, both copper and the seventy two thousand tons of arsenic, which took over in importance from 1860 to 1890, is estimated to have been three and a half million pounds. The lodes extended east and west of the Tamar and suggestions were constantly put forward that the ECMR be linked with the Plymouth, Devonport and South Western Junction Railway (the L&SWR subsidiary responsible for the Plymouth-Tavistock link) but by the time the lines were connected via an impressive viaduct the mineral trade had disappeared. Although copper and arsenic remained the chief exports of the area a number of other minerals[xxxix] were mined and quarried including small amounts of gold.[xl]

In 1925 the last line was built, Torrington to Halwill Junction, though projected routes for this line had appeared on maps at least 60 years before a rail was laid! Bacon's County Atlas of 1869 seems to have been the first to indicate a line south of Torrington. This was soon followed by representations of lines on Heydon's large map of 1872 and on Philips County Atlas map of 1874. The Heydon map, produced by Bartholomew, was perhaps the most influential, being used by W H Smith, Black's guides and Murray's handbooks. It showed the completed line to Bideford and a proposed line from Bideford to Torrington. From there the line was drawn continuing to Little Torrington, skirting Hatherleigh to the southwest before travelling eastwards to meet the (projected) L&SWR line Exeter to Tavistock at Greenslade, just south of Sampford Courtenay. A branch line runs from Hele Bridge (just north of Hatherleigh) due west to Holsworthy and thence to Bude. James Jervis produced a map of the proposed railway c.1897 which varies from Heydon's in that the line continued south after Hatherleigh, linking with the L&SWR line at Okehampton (and ignoring the branch to Holsworthy).

Colonel H Stephens planned the Devon and Cornwall Junction Light Railway to bridge the Torrington gap and partly follow the track of the old Marland light railway; indeed the prospect of carrying clay, cattle and Welsh coal as well as tourists was a reason for its construction.[xli] As built, the line varied slightly as it meandered from Petrockstow to Meeth (Halt) before arriving in Hatherleigh. From there it progressed in a south-westerly direction to Hole before joining the Okehampton-Bude line at Halwill Junction. It finally opened on 27th July 1925.

The railway network in Devon was complete to operate as such for only thirty eight years when the Beeching plan closed many of the branch lines. During the 1960s alone Devon lost some forty stations from its total of nearly one hundred and twenty; a loss of one-third!

In addition to the established lines other railroads and tramways, operated by independent companies, appear on some maps: the Zeal Tor Tamway to Shipley Bridge (1854-1890), and the Lee Moor Tramway to Plymouth (1854-1960), both built for the extraction of minerals from Dartmoor (shown for example on the Bartholomew /Black maps c.1862). There are also others which did not appear such as the Great Consols line west of Tavistock, which ended in the inclined plane down to the quays at Morwellham on the Tamar. This first operated in 1856 and was fully completed in 1859. The line included a loop to Wheal Emma (named in honour of the widow of William Morris, who had been one of the main shareholders).[xlii] Another line which did not appear was the Exeter Railway, though incorporated in 1883, it was only completed from Teign House to Exeter in 1903.

The progress of the railways is reflected in the county maps but to use them as a guide to the dates of various states requires care. Some publishers noted the applications to Parliament for new lines and showed them falsely in anticipation. Examples of these are the line from Newton Abbot directly to Ashburton, and not via Totnes as it was later built (Archer/Dugdale 1858, Wood 1855); the incorrect eastern route from Barnstaple to Ilfracombe (Besley 1866, Murray 1865, Bartholomew 1878); a line from the south west to South Molton (Archer/Dugdale); and the line right round the town of Tiverton (Stanford 1878).

As a good example of the confusion one need look no further than the Archer/Dugdale series (119). The Bristol & Exeter Railroad to Exeter appears on maps in editions usually dated c.1842, although it was not to be opened until 1844. In amended maps, published c.1850, the South Devon Railway is shown to Devonport, the Taw Vale Railway to Barnstaple, the Exmouth Railway to Exmouth and the Dartmouth line to Kingswear, to be opened respectively in 1848, 1854, 1861 and 1864. Another, later, 1850 state showed lines to South Molton from Umberleigh Bridge, and to Ashburton (from Newton Bushell), neither of which was built and both were to be erased on later editions. The surveyor or engraver was probably aware of the various Acts of Parliament or delays or cancellation due to lack of funding and adjusted the maps accordingly. Another example was the line to Kingswear which was taken to Torre in 1848, then suffered hold-ups during the building of the Greenway Tunnel only reaching Paignton in 1859, Churston in 1861, Kingswear in 1864 and with a spur to Brixham built in 1868. To some extent the states reflected the position. For example, in 1858 the Dartmouth line was shortened to Torquay, with roads and estuary redrawn and the Credition-Bideford line was erased only to be reinstated to Barnstaple two years later. The final state of the map, a later in 1860 state, showed the line to Tavistock and the line into Cornwall, both opened in 1859, and the removal of uncompleted lines. Joseph Archer had state and date at last in concert. Look also at Black’s 1855 map which incorrectly shows the line from Exeter to Exmouth not to be completed until 1861 and also shows two lines from Exeter to Crediton, the projected line never to be built (130)

The Becker/Kelly series (132) is a good example of erroneous railway information. The early maps showed a line to Ashburton via Newton Abbot, but later states corrected this to the correct line via Totnes. Two Somerset lines, never completed, were shown from Bridgewater to Stolford in 1860 and Watchet to Dulverton in 1873.

But perhaps the most interesting example was the line from Barnstaple to Ilfracombe. The Besley map of North Devon was first issued in 1857 (134) and showed with a pecked line the mapmaker’s expected route. This showed the line running north through Pilton and Bittadon to just south of Berry Narbor before approaching Ilfracombe from the east. A later state shows the line completed but still wrong. It is now shown running west along the estuary to Heanton Punchardon before turning north to Wrafton and Braunton and passing two miles east of Mortehoe to approach Ilfracombe from the west! Traces of the earlier proposed line can still be seen on this state. Finally we have the actual line through Wrafton which stopped at Braunton and with a noticeable S-bend ran into Mortehoe before reaching Ilfracombe.

Later editions of Philip's Handy Atlas have an interesting alteration to the Kingsbridge line. Although not completed until 1894 the line was shown in 1873 as closely following the river and it was not until 1895 that the line was redrawn correctly, some distance east of the river, and to include Gara Bridge and Doddiswell stations.

[i] J Smeaton; A Narrative of the building of the Eddystone Lighthouse; London; 1791.

[ii] Martin Smith; 1993; p. 105.

[iii] F Booker; 1967 (1974).

[iv] Helen Harris; The Haytor Tramway & Stover Canal; Peninsula Press; 1994.

[v] David St John Thomas; Regional History of the Railway -The West Country; David & Charles; 1960.

[vi] Bryan Gibson. Plymouth Railway Circle; 1997

[vii] Sir R. Lethbride; The Bideford & Okehampton Railway; Devon Assoc. trans.XXXIV-1902.

[viii] C G Harper; The Exeter Road; Chapman & Hall; 1899.

[ix] Daniel Gooch; later knighted; a locomotive engineer and designer who joined Brunel in 1837. He also wrote in his diary that his back was so sore from working on the footplate that he could hardly walk the next day.

[x] Cecil Torr; Small Talk at Wreyland 1st series; Cambridge; 1918.

[xi] David Keir; 1952; p. 137.

[xii] Victor Thompson; 1983; pp. 18 and 30. The South Molton line was shown on Archer/Dugdale (119.5).

[xiii] W W Hutchings; in The Rivers of Great Britain. See entry 176.

[xiv] J Lloyd Page; in The Rivers Of Devon. See entry 170.

[xv] Isabel Brunel; Life of I K Brunel; Longmans Green; 1870.

[xvi] J S Jeans; Railway Problems .

[xvii] P S Bagwell; The Transport Revolution from 1770; 1974.

[xviii] The journey took 4 hours to Bristol and 1 1/2 more to Bridgewater.

[xix] Alfred Wheaton; The Handbook of Exeter; (1845).

[xx] Thomas Latimer writing in The Western Times.

[xxi] R S Gregory; South Devon Railway.

[xxii] Deposited Plan 148 - Devon Records Office.

[xxiii] J Dilley; The Devon Historian; Oct. 1988.

[xxiv] Reported in the Exeter Flying Post.

[xxv] In 1838 by Messrs Clegg, Samuda & Samuda.

[xxvi] Newspaper article of the time.

[xxvii] Newspaper article of the time.

[xxix] The Exeter and Crediton Act of 1845 .

[xxx] The GWR abandoned the broad-gauge for all main lines on 20th May 1892.

[xxxi] Time Tables Great Western and other railways in connection Bristol And Exeter Railway To Plymouth; South Devon Railway To Plymouth; Cornwall Railway To Falmouth; West Cornwall Railway To Penzance. June 1865. Price One Penny. London: Henry Tuck. f/s 1971.

[xxxii] Victor Thompson; 1983; p. 36.

[xxxiii] Victor Thompson; 1983; pp. 30-33.

[xxxiv] F Booker; 1967 (1974); pp. 204-209.

[xxxv] Victor Thompson; 1983; p. 42. Sir George Newnes also supported and financed the Lynton Cliff Railway.

[xxxviii] The following account is taken from F Booker; 1974; especially pp. 22-23.

[xxxix] Besides copper and arsenic, tin, silver, lead, wolfram, and pyrites were extracted. The line was also used for the transport of bricks, tiles and granite.

[xl] In 1999 exploration took place at a recently discovered site in Devon to ascertain whether gold could be mined in viable quantities. See Andrew Mosley; The Quest for Gold; in Devon Today; Devonshire Press; Torquay; January 1999

[xli] Victor Thompson; 1983; p. 37.

[xlii] D B Barton; The Mines of East Cornwall and West Devon; Truro;1964.

No comments:

Post a Comment